By: Justin Lindemann, Senior Policy Analyst

With the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) in early July, Congress is now focusing on advancing the federal budget for fiscal year (FY) 2026, including funding for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). The program is facing significant pressure from the current administration, which has proposed eliminating LIHEAP entirely and has already laid off the federal office staff. While complete elimination remains unlikely, given the bipartisan support typically required to pass a federal budget, the program’s steadily shrinking funding and increasing political pressure raise serious questions. If this nearly 50-year-old lifeline for vulnerable households weakens, especially as utility bills rise, what actions can states and utilities take to fill the gap?

LIHEAP Under Federal Scrutiny

The Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) is a federal initiative with roots in the 1970s oil crisis, which highlighted the need for a national program to help households afford their energy bills. Modeled after Maine’s “Project Fuel” and created in response to the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, the federal government launched the Emergency Energy Conservation Program later that decade. Initially focusing on weatherization assistance, it later expanded to direct bill support for low-income households. One of the earliest federal energy assistance programs, LIHEAP was formalized in 1981. Since then, it has provided funding for operations in every state, the District of Columbia, and most U.S. territories and tribal nations, helping prevent energy-bill crises by providing payments directly to utilities, fuel suppliers, and households, and has a +58 approval rating from individual Americans. LIHEAP is also commonly used to determine income eligibility for various other state and utility assistance programs.

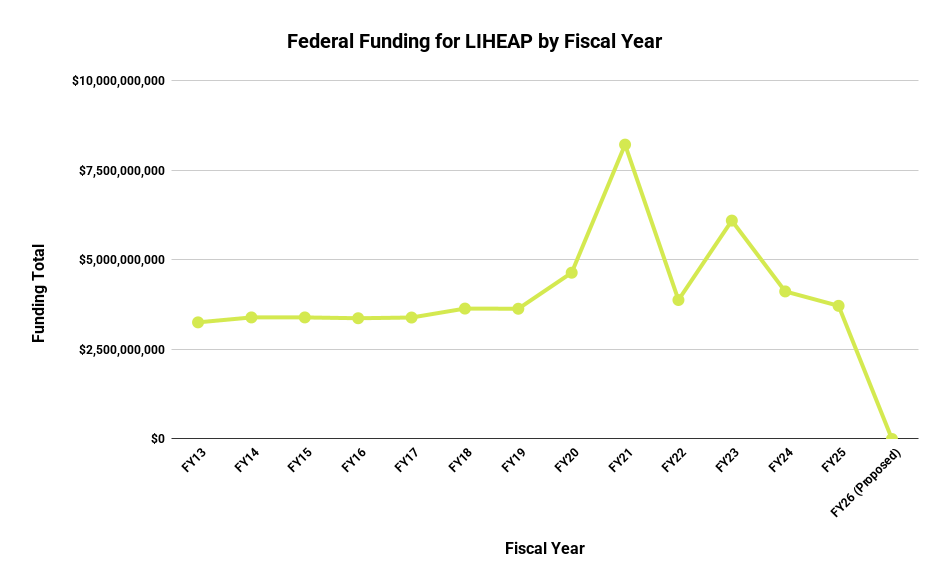

However, access to the federal program has become increasingly limited as funding returns to pre-pandemic levels. Funding for FY2024 was drastically decreased by $2 billion – from approximately $6 billion in FY2023 to just over $4 billion – resulting in reduced services for over one million low-income households. In FY2025, funding fell even further to below $3.7 billion, inching closer to the budget totals before FY2020 and further away from the $8.2 billion peak in FY2021, during the height of the pandemic.

Now, as Congress turns its attention to the FY2026 budget following the early July passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) along party lines, LIHEAP faces heightened scrutiny. The Trump administration’s FY2026 budget proposal, released in May, calls for eliminating the program. The proposal labels LIHEAP as “unnecessary,” citing “fraud and abuse” based on a 2010 Government Accountability Office audit.

The proposal notes that many states already have policies in place that prevent utility disconnections for low-income households. While this is true, such protections do not address one of the main purposes of LIHEAP – providing payment assistance to households struggling to afford their energy bills. Disconnection moratoria may prevent immediate shutoffs, but they do not address the underlying debt burden that would accumulate in the absence of federal energy assistance. As a replacement, the administration suggests supporting low-income individuals through “energy dominance, lower prices, and an America First economic platform.”

Graph (above) illustrating total federal funding for LIHEAP by FY, from FY2013 through the Trump administration’s proposed funding level for FY2026. Chart: Justin Lindemann, NC Clean Energy Technology Center; Data Source: LIHEAP Clearinghouse

One month before the proposal’s release, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) abruptly fired the entire federal LIHEAP office, approximately two dozen staffers, leaving the program without any federal representation. This severely undermines its ability to coordinate with states and calculate and administer current and future state-by-state funding. In response, a bipartisan bill in the House, known as the LIHEAP Staffing Support Act, would require a minimum staffing threshold of at least 20 for the program, and at least 30 in cases of emergency.

Although Congress has long relied on continuing resolutions—extending previous FY funding levels rather than passing new budgets—the political momentum behind the OBBB’s passage may signal a turning point. Growing executive pressure could fuel rising congressional opposition to the widely supported federal energy assistance program, potentially shaping future funding decisions. This pressure is intensified by a recent Supreme Court ruling affirming the administration’s authority to downsize federal agencies. The DHHS firings exemplify this power in practice and raise serious concerns about LIHEAP’s ability to function effectively, even if funds are appropriated, in the absence of essential program staff.

Moreover, while the Senate’s FY 2026 appropriations recommendations for DHHS increase LIHEAP funding by approximately $20 million to a total of $4.05 billion compared to 2025, the House is not expected to review its version until September, ahead of the October start of the new FY. As previously noted, a significant cut to the federal program remains unlikely. However, the executive branch’s authority to reduce staffing could still undermine the effectiveness of any appropriated LIHEAP budget.

Rising Utility Bills

As LIHEAP funding returns to pre-pandemic levels and faces renewed opposition from the current administration, the need it serves remains unchanged. Utility bills are rising nationwide, and an estimated 73% of Americans across the political spectrum are concerned that bills will continue to increase this year. Combined with the broader inflationary pressures on essential goods like food, the highest burden falls the heaviest on low-income households.

One major driver of these increases is the projected surge in data center development, which is prompting utilities to build new generation infrastructure and pass associated costs on to ratepayers. Compounding this, the OBBB shortened the eligibility for key solar and wind tax credits to the end of 2027, while imposing additional eligibility constraints related to foreign material assistance and operational dates, thereby undermining future development of the nation’s lowest-cost and fastest-to-deploy energy sources. Meanwhile, advanced nuclear projects remain years away from commercialization, and new natural gas plants in the country face lengthy construction timelines of up to seven years. The narrowing of tax credit access for solar and wind—while subsidies remain for technologies like nuclear, geothermal, and hydropower—will likely lead to higher rate increases for residential customers as utilities seek to combat new load sources and increased prevalence of extreme temperatures.

According to the Clean Energy Buyers Association, eliminating tax credits for clean energy would result in significantly higher residential bills. While OBBB didn’t go that far, its impact would still raise costs as two near-term resources lose financial support. Even a partial rollback, layered on top of existing inflation, compounds financial pressure on households already struggling to make ends meet.

Chart (above) describing the projected percentage increases in residential electricity utility bills by state through 2029, compared to current levels. Chart: Justin Lindemann, NC Clean Energy Technology Center; Data Source: Clean Energy Buyers Association.

Given these trends and the federal headwinds facing LIHEAP, state and utility programs have an opportunity to fill the gap and support the millions of low-income families at risk of falling behind on their energy bills, in case the federal program is left largely ineffective.

Existing Levers for Assistance

Amid severe and unpredictable federal budget and program personnel fluctuations, states and utilities have an opportunity to fill the performance and funding gaps in the LIHEAP program. Some state lawmakers have expressed support for this approach in light of the current administration’s stance on federal heating and cooling assistance. In Kentucky, for example, officials are considering stepping in to offset a potential loss of more than $50 million in funding, which currently supports an estimated 150,000 households.

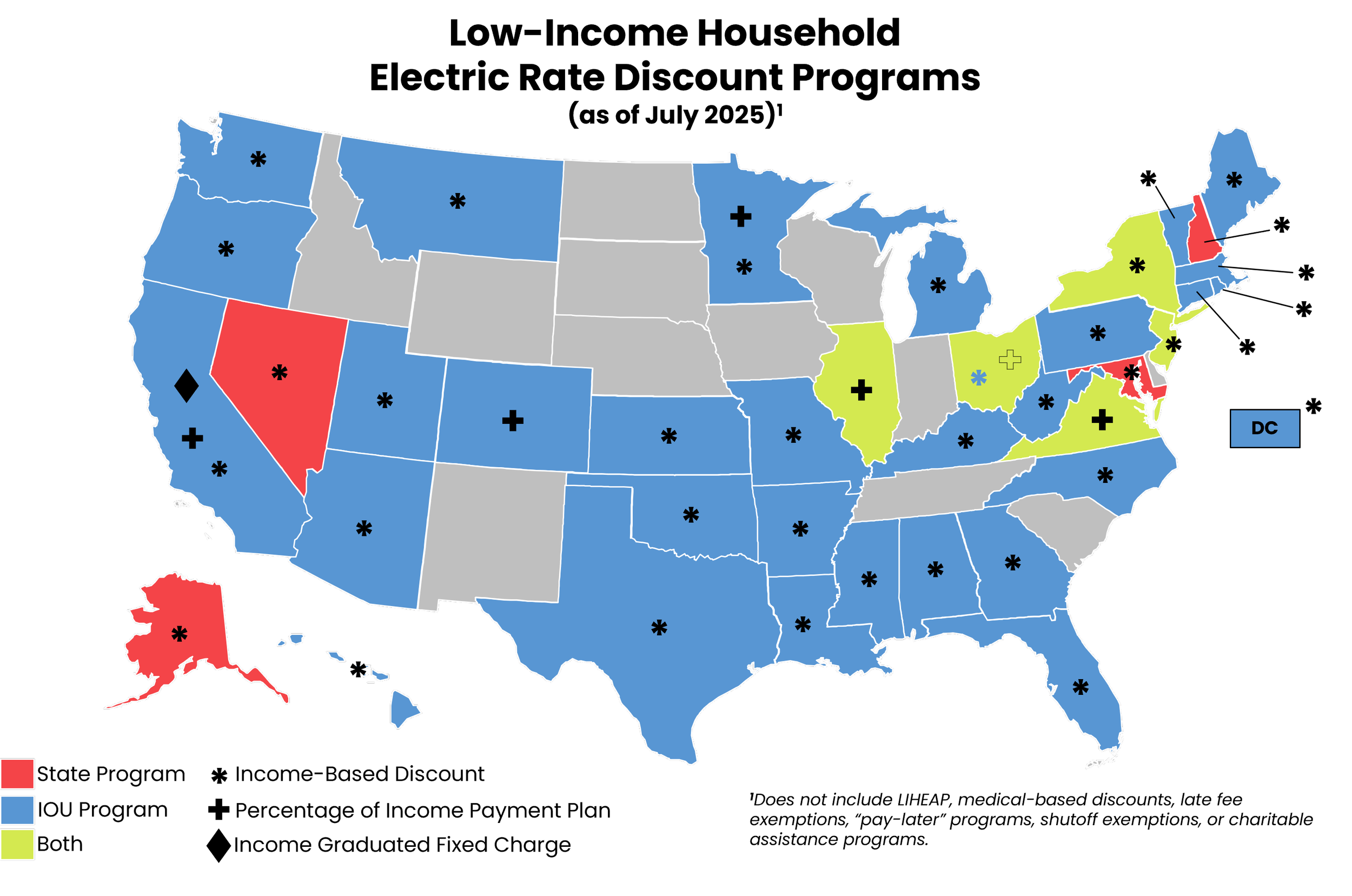

Moreover, many state and utility-run assistance programs already exist, varying in scope and structure. These include income-based discounts, percentage of income payment plans (PIPPs), income-graduated fixed charges, and other supports such as exemptions from late fees or shut-offs.

Income-based discounts typically reduce or eliminate fixed charges or apply a percentage discount to a customer’s total monthly bill, depending on income eligibility. These may be offered as one-time or ongoing benefits, and can be implemented through income-based tiers.

PIPPs are payment plans that cap a customer’s monthly utility bill at a set percentage of household income, generally no more than 10%. Some plans also consider the home’s primary heating source when determining payment levels. Similar to income-driven student loan repayment, PIPPs help low-income households manage energy costs, freeing up income for other essentials such as food, housing, or savings.

Another approach is the income-graduated fixed charge, recently approved in California. This model, inspired by progressive taxation, reduces fixed charges for lower-income customers and increases them for higher earners. It represents a significant shift in rate design for investor-owned utilities in the state, many of which previously did not include fixed charges at all.

Currently, a majority of states have at least one major utility offering a low-income electric rate discount. In November 2024, Duke Energy Florida received approval to provide a monthly bill credit for income-qualified customers, excluding net metering participants, to offset the existing $30 minimum bill charge. If such a customer receives a bill reflecting the minimum charge, Duke Energy will manually apply a future credit, so the bill reflects only the customer charge plus actual electricity usage. Eligibility is based on current participation in various federal and state low-income assistance programs such as Medicaid, LIHEAP, or Duke’s Neighborhood Energy Saver, among others.

Some states go further by offering PIPPs. Ohio’s PIPP Plus caps monthly utility payments based on income, specifically 5% for gas and 5% for electricity in gas-heated homes, or 10% for electricity in electric-heated homes, with a minimum bill of $10. After 24 consecutive on-time payments, the remaining debt is forgiven. In contrast, New Jersey shifted its Universal Service Fund from a PIPP to a traditional low-income discount program. Meanwhile, California remains the only state to implement an income-graduated fixed charge.

Map (above) depicting the various low-income household electric rate discount programs that state and/or electric investor-owned utilities offer as of June 2024. The map does not include LIHEAP, medical-based discounts, late fee exemptions, “pay-later” programs, shutoff exemptions, or charitable assistance programs. Source: Justin Lindemann, NC Clean Energy Technology Center.

In the Northeast, Connecticut and Massachusetts are pursuing significant regulatory changes to improve affordability. In late October 2024, the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA) issued a draft decision to expand the state’s low-income discount rate program from two tiers to five, with discounts ranging from 10% to 50% based on income. The draft also rejected utility proposals to narrow eligibility and introduced a 2% program cost cap based on annual revenues. The final decision, issued a month later, retained the five-tier structure but adjusted discounts to meet the cost cap: 5%, 15%, 20%, 40%, and 50% for Tiers 1 through 5, respectively. PURA then issued another decision in mid-March this year, directing utilities to transition customers to their new eligible tiers as soon as the revised discount rate is operational, rather than waiting for the full 12-month enrollment cycle to expire.

In Massachusetts, the Department of Public Utilities (DPU) launched an inquiry in January 2024 to explore affordability solutions, including tiered discount rates (TDRs) and PIPPs. Utilities expressed support for TDRs, referencing New Hampshire’s model, and opposed PIPPs due to the administrative complexities associated with them. In early September 2024, the DPU issued an order affirming several principles: programs should cap energy burden at 6%, be based on income and household size, include both heating and non-heating customers, protect customers with outstanding bills, and extend shutoff protections during extreme heat or poor air quality. The DPU chose to focus on tiered discounts over PIPPs, and a Phase II stakeholder working group was convened in mid-May 2025 to address remaining issues, including the design of the tiered discount program, income verification, and utility disconnection policies.In the Northeast, Connecticut and Massachusetts are pursuing significant regulatory changes to improve affordability. In late October 2024, the Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority (PURA) issued a draft decision to expand the state’s low-income discount rate program from two tiers to five, with discounts ranging from 10% to 50% based on income. The draft also rejected utility proposals to narrow eligibility and introduced a 2% program cost cap based on annual revenues. The final decision, issued a month later, retained the five-tier structure but adjusted discounts to meet the cost cap: 5%, 15%, 20%, 40%, and 50% for Tiers 1 through 5, respectively. PURA then issued another decision in mid-March this year, directing utilities to transition customers to their new eligible tiers as soon as the revised discount rate is operational, rather than waiting for the full 12-month enrollment cycle to expire.

Conclusion and Looking Forward

As Congress tries to advance a FY2026 budget following the passage of the OBBB, the future of federal energy assistance, like LIHEAP, is put under pressure. Though full elimination remains unlikely, the program’s already low funding, administrative disruption, personnel problems, and mounting political pressure raise legitimate concerns about its long-term viability. With the national energy landscape evolving and utility costs climbing, any reduction or roadblocks that could undermine this nearly 50-year-old safety net could affect millions of households facing high and growing energy burdens.

At the same time, factors such as inflation, the expansion of data centers, and adjustments to federal clean energy tax policy are contributing to higher energy prices, particularly for low-income customers. While the narrowing of solar and wind incentives through the OBBB is likely to increase reliance on more expensive or slower-to-deploy resources, potentially adding to long-term affordability challenges. These factors raise the importance of Congress significantly increasing LIHEAP’s federal budget beyond what has been appropriated since the pandemic was deemed over, to meet the energy affordability issues facing low-income households.

In the face of this uncertainty, state legislators, utility regulators, and utilities themselves are taking the initiative. From Duke Energy Florida’s minimum bill credit discount to California’s income-graduated fixed charge, forward-looking affordability strategies are emerging across the country. Connecticut and Massachusetts are taking meaningful steps to redesign and expand their low-income discount programs, moving beyond traditional structures toward more equitable and refined income-based models that may address the concerns of today’s households.

As the policy landscape shifts, the role of states, regulators, and utilities in addressing energy affordability is likely to become increasingly important. Proactive measures at these levels may help close gaps and support households most at risk from rising costs.