By: DSIRE Insight Team

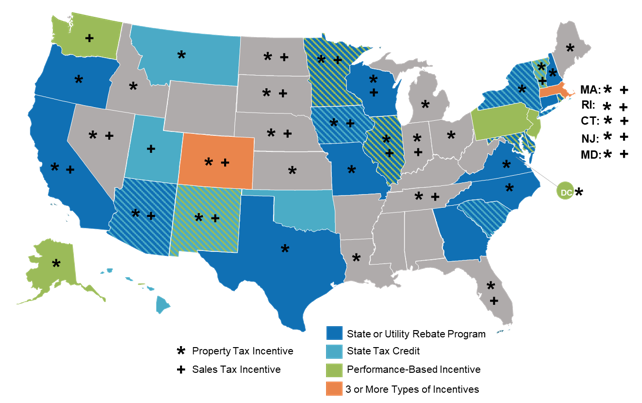

Many states and utilities offer a variety of financial incentives for solar photovoltaics (PV) in order to encourage solar adoption and achieve state solar development goals. As the cost of solar has declined, many states have phased out their incentive programs. However, at least 44 states offer at least some type of financial incentive for solar energy, with property tax exemptions being the most common type of incentive.

State and Utility Solar PV Incentives (August 2020)

Tax Credits

At the federal level, solar energy projects are eligible for a 26% investment tax credit. This credit will decrease to 22% in 2021 and again to 10% in 2022. The credit will remain at 10% for commercial projects, while the credit will expire completely for residential projects at the end of 2021.

In addition to the federal investment tax credit, 9 states currently offer income tax credits for which solar is an eligible technology. New Mexico lawmakers enacted legislation earlier in 2020 bringing back a revised version of its expired Solar Market Development Tax Credit, which provides a credit for 10% of system costs up to $6,000.

Rebate Programs

State or utility solar rebate programs currently exist in 17 states (including only utilities with at least 40,000 customers). Most rebate programs provide an incentive based on the capacity of the solar system, while a few provide a flat incentive. Most rebate programs provide incentives between $0.20 per Watt and $0.75 per Watt, with some incentives providing as much as $3.00 per Watt.

The Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy is currently developing a solar rebate program focused on low to moderate income customers, pursuant to legislation enacted earlier in 2020. The legislation specifies that the incentive may be up to $2.00 per Watt.

Performance-Based Incentives

At least 11 states and DC offer performance-based solar incentives that provide a per-kWh payment to project owners based on actual system production. Xcel Energy’s Solar*Rewards program is an example of a performance-based incentive, where Colorado and Minnesota solar owners can receive payments ranging from $0.005 to $0.07 per kWh of production.

A number of states that have solar energy carve-outs within their renewable portfolio standards also have active markets for Solar Renewable Energy Certificates (SRECs). An SREC represents 1 MWh of solar energy, and electric power suppliers must generate or procure a certain number of SRECs to comply with their state’s standard.

Property and Sales Tax Incentives

Property and sales tax incentives are the most common types of solar incentives across the country. Thirty-six states have adopted property tax exemptions for solar energy systems, or authorized local governments to implement property tax exemptions. While the majority of these exemptions apply to the full added value of the solar installation, some states’ property tax incentives apply to a percentage of the added value or allow an exemption for only a certain number of years.

Another 22 states exempt solar energy systems from sales taxes. Like property tax incentives, most sales tax incentives for solar provide a full exemption. In Washington, solar energy systems up to 100 kW are eligible for a full sales tax exemption, while systems over 100 kW and up to 500 kW are eligible for a 50% exemption.

* * *

Learn more about incentives for solar energy with the DSIRE Insight Solar Single-Tech Subscription ($4,500 per year) or the Solar Policy Data Sheet ($500). Contact us for more information.